a provocation.

Challeng-portunities of leadership in 2025:

:: SELENA’S PROVOCATION ::

So I should start by introducing myself. My name is Selina Thompson, I’m an artist and writer and the AD and CEO of Selina Thompson Ltd, a performance company which will be ten years old next year. I am disabled, and Black and a woman, and these are things that factor into my leadership, and how we choose to run our company. I am committed to care, and the company’s values centre integrity, equity, dignity and the importance of art. We also place sustainability high on our priorities; in particular, sustainable ways of working with the mind, body and soul in performance. We believe that the structure is the thing – the space where an experimental approach can truly live, and we try to lead from a principle of finding the best answer, not on having certain people holding authority on answers because of where they sit in a structure. We are not always successful at this! In the past couple of years especially we have made lots of mistakes. But these are the aspirations.

I’ve been asked to speak about the challenges and opportunities of leadership: and to my mind, these are the same thing. They are chinks of possibility where change becomes necessary – and sometimes that feels heady and exhilarating, like the opportunity to work in ways you have always wanted to try, and in other ways that feel nauseous and terrifying, like finding that the way you have always worked is no longer an option for you. But the chink of possibility, which can go either way, is always the same. So we’re going to use the word challenge here, but I always mean opportunity. And when I say opportunity I always mean challenge.

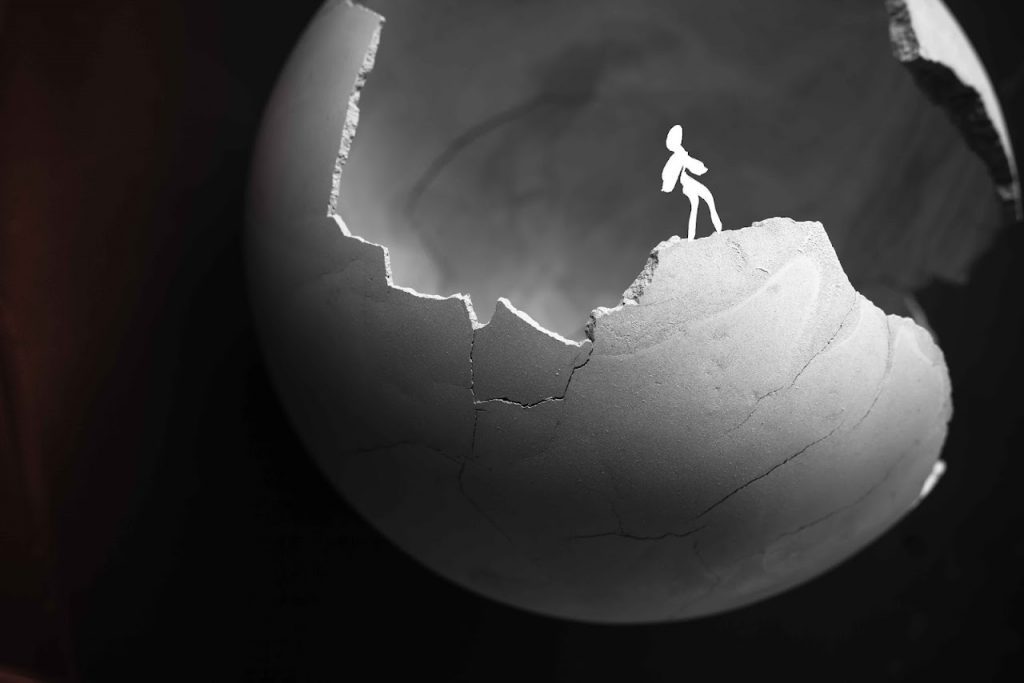

CEMENT PARTY SCULPTURE AND PHOTOGRAPH BY SONIA LEVESQUE

So what are the challeng-portunities of leadership in 2025?

The first thing I wrote down when considering the challenges of leadership was how not to be overwhelmed into stillness. Stillness is maybe not the right word – maybe I mean inertia. Stillness, held, can be a real strength in leadership. And you’ve got to know the difference. But how does one remain engaged in the world, when the world is so violent and frightening, and aspire to change it?

When you drive past the flags, which further down the road become a bloody protest outside the hotel, when you return from the protest about Gaza to a news report on how aid cannot get through the borders to alleviate the famine, when the left in-fighting escalates in tandem with Reform’s electoral success, when each new day is an announcement from Trump or Putin or both, when no country seems safe from a slick slide to the right, and still the planet is burning, burning, burning. How exactly does one look at all this and not become paralysed by fear?

I don’t have an answer to this (it’s not the part of the talk for answers yet. And I’m terrible at answers, there will be no answers, I’m more interested in a leadership built out of questions, listening, and the structures for the best questions and the best listening). I wanted to name this as the greatest challenge (or at least the one I wrestle with most intensely) to keep moving, to maintain action beyond dialogue and stay engaged in struggle in whatever way you can.

Like most challenges, it can be broken down into a series of smaller challenges. Maybe this is really the challenge of picking your battles and then maintaining a commitment to them. There is much to be said for a dogged commitment to one issue, to carefully measuring your energy and the energy of your organisation and deciding that it will flow in one key direction, and stay that course, even as other things come up. To being devoted to a single issue above all else, and acknowledging that your energy is finite.

This is particularly valid in a context in which we all have to do less with more, because that is what is continually asked of us. How do we push back against this? Because its unsustainable at its core. We know now that there is less money than there was, and that that money sits in the hands of fewer people and organisations – if the National Theatre is reducing some of its teams from 24 to 7, where does that leave the rest of us? How do we have grace about this when working in arts and culture can already be perceived as the realm of a privileged few: especially the privileged few that get to lead?

Some challenges are disguised as opportunities and vice versa. What is it to be a leader at a moment in time when we are really questioning what leadership is and what it should look like? Old models – like that of a single white man drenched in charisma leading everybody else (while a group of women bustle about just beneath him doing all the actual *work*) – feel increasingly antiquated (or do they? I still see it all around…). So what are the new models of co leadership that we want to build? What are the mistakes we must make along the way? What are the red herrings, the things that seem new but are actually business as usual?

One of the biggest challenges of any kind of change is that an old model can be replaced by a new one – but all the assumptions and culture that surrounded the old model can remain in place. How is change more than skin deep? How are changes embedded in an organisation systemically and procedurally, so that they are not vulnerable to changes in team members?

Our workplaces look and feel different. I keep thinking about workplaces that use generative AI, and what its increasing impingement into daily life tells us about the speed and intensity of technological change, and our capacity to keep our ethics and values ahead of these changes. Of all the ways in which those working in the mainstream of culture didn’t heed the warnings and worryings of those on the fringes. What do we assume is the flow of knowledge, and how can we think outside of those assumptions? How do we spot canaries in coal mines quicker?

You must be wondering why someone with so many questions and so few solutions has been invited to speak with you.

So I think the last time I was here – and remember they invited me back! – I spoke about how all the challenges are – not the same as ever – but how constant challenge is the nature of leadership, and those stakes are only going to get higher, those changes more intense. And maybe a little bit I kind of told folks to suck it up? Oh god that’s really mean. But I think I was speaking from a place where every year I have been in the arts ecology – so since about 2012 – I have listened to folks talk about things being bad, worse than ever, the worst they’ve have ever been. And when that’s all you’ve heard, it starts to lose its meaning.

So I don’t think folks should suck anything up, there should be space for grief and for dread and for panic. But I do think we need to be resilient and pragmatic about change, and somewhat stoic. And by stoic I don’t mean without emotion – there should always be time for us to feel what we need to feel in fullness – but I do mean accepting of times being difficult now with greater difficulty to come. And if you are called to lead, you are also called to bear that in very specific ways.

So we have to be resilient as leaders. What is the key to that? It can’t be creating models where we don’t fail, or burn out or are flawless, as we know this is impossible, and our leaders have to model what is sustainable, and realistic. Perhaps it is that we commit to murmuration and leadership that shapeshifts. Perhaps it is that we commit to building strong friendships between leaders so that we can fall on each other when we need to. Perhaps we need leaders that speak with their vulnerabilities first, and encourage us to perceive them as strengths, also. Perhaps our leadership looks like living a rich and fulfilling civic life, so that we know that all of our activisms, all of our standing up to and for and against doesn’t have to come from one source, rather, it can come from many.

I’ve been having some leadership coaching recently. Which feels extremely decadent, the richest of treats. When I was asked what I needed to be a resilient leader, I was struck by how dependent I was on other people and also being able to be fully human with other people. I wanted transparency, collaboration and vulnerability. I wanted to be held and encouraged to put my ego to the side, and I wanted accountability and feedback. I wanted more time for dreaming. I was surprised by the delicacy of these requests in some ways. But in other ways, they feel in keeping with all the goals of the company, and with the kind of person I want to be in other parts of my life. So maybe consistency is part of what we need to be resilient leaders.

Or maybe resilience is overrated. Maybe there is something stiff, and rigid, and liked a clenched jaw about always being ready to ride the next wave – and our time would be better spent being wave like, and soft, embracing uncertainty with a deep breath and a turn to an ally or comrade. Maybe that is the big one, the core challeng-pourtunity. To be like water, loose and flowing in response to change.

When I wrote this, I immediately thought ‘but I am an earth sign – in many ways the opposite of water. I’m solid, and firm and fixed’ – but this isn’t true of soil flowing through my fingers, or the oozing gooey slide of mud. And I thought about how another challenge-pourtunity of leadership is to see yourself in a whole new way, to rethink your assumptions about yourself, and about leadership itself to make something new, to reach new depths of knowledge about yourself and the world around you. And that felt like a good provocation to end on.

A Provocation by Selina Thompson, Artistic Director and CEO of Selina Thompson Ltd

=========

::ABOUT COLLECTIVE::

(via https://www.culturecentral.co.uk)

For Collective 2025, Selina Thompson was one of a series of speakers and facilitators that launched this year’s programme with twelve members of this year’s Collective at a residential in Solihull from 29th September to 2nd October. This guest blog post shares Selina’s reflections on the challenges and opportunities of collective leadership in 2025.

Collective is leadership programme, that explores collaborative and collective approaches to sector change for those traditionally excluded from senior roles in the cultural sector. Collective takes an intersectional approach and aims to avoid working in a deficit model, focusing instead on the structures that limit and exclude.

As a programme, Collective accumulates and builds each year, with the cohort maintaining a relationship with Culture Central to embed, share and support change. Through this iterative and collaborative programme, we want to make strategies and actions together for change. Collective, alongside Culture Central’s other programmes, activities and networks is integral to our role and commitment in supporting change.

=========

:: PREFER TO READ IN VIRTUAL SPACE? (click on the image)::

writer:

Selina Thompson

. . .

originally published on:

Culture Central

. . .